Transforming Early Childhood Care and Education in India for Universal Access

EDUCATION

Chaifry

5/30/20259 min read

Introduction

Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) is a critical component of India’s educational landscape, focusing on the holistic development of children from birth to eight years, with a particular emphasis on the 3–6 age group. This period is essential for fostering cognitive, socio-emotional, and motor skills, laying the foundation for lifelong learning and school readiness (Ministry of Education, 2020, p. 15). India, with approximately 158.7 million children aged 0–6 (Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India, 2011, p. 25), faces the challenge of ensuring universal access to quality pre-primary education, a goal set by the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 for 2030, aligning with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4.2 (UNICEF, 2019, n.p.).

Currently, nearly 80% of children aged 3–6 are enrolled in ECCE programs, but disparities in quality and access persist, particularly in rural areas and among marginalized communities (Pratham, 2018, p. 10). The Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) operates 1.4 million Anganwadi centers, serving over 80 million children, yet only 50% of educators are adequately trained (Ministry of Women and Child Development, 2023, p. 22). Private pre-schools, enrolling nearly half of urban children, often lack regulation, leading to inconsistent quality (UNICEF India, 2020, n.p.). Achieving universal ECCE requires addressing systemic challenges and scaling effective models, a task complicated by funding cuts, teacher shortages, and governance fragmentation.

This article explores the factors needing improvement to provide pre-primary education to all children aged 3–6, proposes a timeline for achieving universal access, and outlines strategies to overcome barriers, drawing on government reports, longitudinal studies, and state-level initiatives.

Historical Policy Evolution

The evolution of ECCE policies in India reflects a gradual shift from neglect to prioritization. The NEP 1968, based on the Kothari Commission, focused on universal elementary education up to age 14, establishing the 10+2+3 structure, but overlooked ECCE, leaving pre-primary education informal and community-driven (Ministry of Education, 1968, n.p.; Teachers Institute, 2023, n.p.). The NEP 1986 marked progress by recognizing ECCE’s role in school readiness, targeting 70% coverage for children aged 0–6 by 2000 through 20 lakh ECCE centers, delivered via ICDS Anganwadi’s, though achieving only 30% coverage due to funding and training limitations (Ministry of Education, 1986, p. 12; Ministry of Women and Child Development, 2023, p. 22). The National ECCE Policy of 2013 further emphasized ECCE as a fundamental right, aiming to standardize curricula, but implementation was uneven due to capacity constraints (UNICEF India, 2015, n.p.; Newton Schools, n.d., n.p.).

NEP 2020 positions ECCE as a cornerstone, mandating at least one year of pre-school education and universal access by 2030, supported by the National Curricular and Pedagogical Framework for ECCE (NCPF-ECCE) and the National Curriculum Framework for Foundational Stage (NCF-FS) 2022, emphasizing play-based, inquiry-driven learning (Ministry of Education, 2020, p. 15; NCERT, 2022, n.p.). This policy mandates continuous professional development (CPD) and a 4-year B.Ed. requirement for ECCE teachers by 2030, aligning with modern pedagogies like Reggio Emilia and Montessori (PMC, 2020, n.p.; NCTE, 2023, n.p.).

Factors Requiring Improvement

To ensure all children aged 3–6 receive quality pre-primary education, several interconnected factors must be addressed:

Shortage of Trained Teachers:

Challenge: NEP 2020 mandates a 1:20 teacher-child ratio for 40–45 million children, requiring 2–2.25 million teachers, but only 700,000 exist, with 50% trained (Ministry of Education, 2020, p. 15; Ministry of Women and Child Development, 2023, p. 22). Anganwadi workers, handling 22 children on average, often prioritize nutrition and health, lacking specialized ECCE training (UNICEF India, 2020, n.p.).

Improvement Needed: Expand certificate (6-month CECE) and diploma (1-year DECE) programs to train 1.5–2 million additional teachers by 2030, integrate ECCE into teacher education (NCTE, 2023, n.p.), and implement mandatory CPD focusing on play-based pedagogy (NCERT, 2022, n.p.). Digital training via SWAYAM can reach rural educators, as seen in Tamil Nadu’s 6-day ECCE training model (Government of Tamil Nadu, 2023, n.p.). Increasing salaries from ₹10,000–₹20,000 to ₹30,000–₹50,000 monthly can reduce 30% turnover and address the 95% female-dominated workforce (CSCCE, 2024, n.p.). Assam’s training of 21,521 teachers in 2024–25, including internships, exemplifies scalability (Government of Assam, 2025, n.p.).

Inadequate Infrastructure:

Challenge: Only 10% of 1.4 million Anganwadi’s have child-friendly facilities, with rural centers often lacking furniture, water, and sanitation (Ministry of Women and Child Development, 2023, p. 22). Private pre-schools vary, with urban facilities better equipped. NEP 2020’s emphasis on upgrading Anganwadi’s and establishing Bal Vatika’s is slow, particularly in disadvantaged districts (LEAD Group, 2024, n.p.).

Improvement Needed: Invest in child-friendly furniture, play materials, and sanitation, as seen in Tamil Nadu’s Montessori-based LKG/UKG in 2,381 Anganwadi’s, boosting enrollment by 15% (Government of Tamil Nadu, 2023, n.p.). Expand Bal Vatika’s in government schools, following Uttar Pradesh’s 60,137 co-located centers (Government of Uttar Pradesh, 2024, n.p.). Public-private partnerships (PPPs) can equip rural centers, ensuring compliance with NCF-FS 2022 safety standards (NCERT, 2022, n.p.). Increase state ECE budgets, as Uttar Pradesh did by 46.75% from ₹900 crores (2022–23) to ₹1,300 crores (2024–25) (Government of Uttar Pradesh, 2025, n.p.).

Fragmented Governance and Coordination:

Challenge: ECCE involves multiple ministries—Education, Women and Child Development, Health, and Tribal Affairs—leading to unclear responsibilities. ICDS focuses on nutrition, while Education emphasizes pedagogy, causing inefficiencies, especially in rural areas (UNICEF India, 2020, n.p.).

Improvement Needed: Establish inter-ministerial committees, as in Thailand, chaired by Chief Secretaries for streamlined planning (UNICEF, 2022, n.p.). Develop a convergence framework integrating health, nutrition, and education, as per the Nurturing Care Framework (WHO, 2018, n.p.). Empower states to tailor programs, as in Uttar Pradesh’s alignment with NIPUN Bharat (Government of Uttar Pradesh, 2024, n.p.). Strengthen Poshan Tracker for monitoring, ensuring accountability (Ministry of Women and Child Development, 2023, p. 22). Uttar Pradesh’s ICDS-Basic Education convergence increased enrollment by 10% in targeted districts (Government of Uttar Pradesh, 2024, n.p.).

Lack of Reliable Data:

Challenge: Comprehensive data on ECCE enrollment, attendance, and quality are lacking. ASER 2018 notes one-third of 3–6-year-olds are not enrolled, with state variations poorly documented, hampering planning (Pratham, 2018, p. 10).

Improvement Needed: Create a national ECCE database integrated with UDISE+ to track enrollment, teacher qualifications, and infrastructure (Ministry of Education, 2024, p. 8). Conduct household surveys to capture participation across providers, aligning with global standards (UNICEF, 2020, n.p.). Define quality indicators (e.g., teacher-child ratio, program dosage) per Aadhar Shila’s framework (NCERT, 2022, n.p.). Fund research like the IECEI study to evaluate outcomes (UNICEF India, 2022, n.p.). Tamil Nadu’s assessment cards and child profiles offer a data-driven model, improving effectiveness by 20% (Government of Tamil Nadu, 2023, n.p.).

Inequitable Access and Inclusion:

Challenge: Despite 80% enrollment, only 51% of children from the lowest wealth quintile attend Anganwadi’s, compared to 62% from the highest quintile in private facilities (UNICEF India, 2020, n.p.). Children with disabilities are excluded due to untrained staff and inaccessible infrastructure, with rural areas facing limited access (Pratham, 2018, p. 10).

Improvement Needed: Prioritize disadvantaged districts with mobile ECCE units and community programs, per NEP 2020 (Ministry of Education, 2020, p. 15). Train teachers in inclusive education for diverse learners, including disabilities (LEAD Group, 2024, n.p.). Provide free or low-cost ECCE for low-income families. Implement multilingual curricula, as in Chhattisgarh’s Sanskar Abhiyan, serving tribal minorities (Government of Chhattisgarh, 2023, n.p.). CLR India’s work with 250 Anganwadi’s in Amravati, using Korku language, increased enrollment by 15% (CLR India, 2024, n.p.).

Inconsistent Curriculum and Quality Standards:

Challenge: ECCE quality varies due to unregulated private providers and outdated Anganwadi curricula. Private pre-schools often rely on rote memorization, contrary to NEP 2020’s play-based approach (UNICEF India, 2020, n.p.). Aadhar Shila provides a national curriculum, but implementation is uneven (NCERT, 2022, n.p.).

Improvement Needed: Roll out Aadhar Shila’s competency-based lesson plans nationwide, emphasizing play-based learning (NCERT, 2022, n.p.). Enforce registration for private pre-schools, ensuring NCF-FS 2022 compliance (NCERT, 2022, n.p.). Supply age-appropriate materials, like Tamil Nadu’s activity books, to all centers (Government of Tamil Nadu, 2023, n.p.). Use NIPCCD’s quality indicators to assess classroom management and outcomes (NIPCCD, 2023, n.p.). Assam’s pictorial activity calendar in eight languages enhances accessibility, improving engagement by 25% (Government of Assam, 2024, n.p.).

Insufficient Funding:

Challenge: ECCE is underfunded, with a 7% education budget cut in 2024–25. UNESCO recommends 10% for pre-primary, but India allocates less than 5%, limiting teacher training and infrastructure (UNESCO, 2022, n.p.; PRS Legislative Research, 2024, p. 5).

Improvement Needed: Allocate 10% of education budgets to ECCE, as pledged at the 2022 UNESCO ECCE Conference (UNESCO, 2022, n.p.). Explore CSR and international funding for early childhood development (World Bank, 2023, n.p.). Scale low-cost interventions like NGO-led training. Encourage state-level investment, as Uttar Pradesh increased ECE budgets by 46.75% from ₹900 crores (2022–23) to ₹1,300 crores (2024–25) (Government of Uttar Pradesh, 2025, n.p.). NITI Aayog’s Viksit Bharat 2047 plans signal commitment, aiming for a 20% budget increase by 2027 (NITI Aayog, 2024, n.p.).

Limited Community and Parental Engagement:

Challenge: Parental awareness of ECCE’s importance is low, particularly in rural areas, reducing enrollment and home-based learning. Anganwadi’s often lack community involvement, limiting effectiveness (UNICEF India, 2020, n.p.).

Improvement Needed: Launch media campaigns to highlight ECCE benefits, targeting rural families. Organize monthly ECCE days, as in Tamil Nadu, updating parents and increasing engagement by 30% (Government of Tamil Nadu, 2023, n.p.). Engage NGOs like Pratham for underserved areas, reaching 10% more children (Pratham, 2024, n.p.). Distribute activity calendars, as in Assam, to encourage parental support (Government of Assam, 2024, n.p.). UNICEF’s family readiness programs boost participation by 20% in pilot areas (UNICEF India, 2020, n.p.).

Timeline for Universal ECCE Access

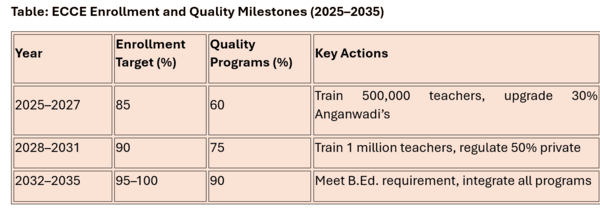

NEP 2020 sets 2030 as the target for universal ECCE access but achieving this for 40–45 million children require a phased approach. Based on current progress and challenges, a realistic timeline extends to 2035, with milestones:

Phase 1: Foundation (2025–2027):

Goals: Train 500,000 new ECCE teachers, upgrade 30% of Anganwadi’s, and establish 100,000 Bal Vatika’s.

Actions: Launch national ECCE training via SWAYAM (Ministry of Education, 2024, p. 8), increase ECE budgets by 20% annually (Government of Uttar Pradesh, 2025, n.p.), develop a centralized ECCE database (Ministry of Education, 2024, p. 8), and pilot Aadhar Shila in 50% of states (NCERT, 2022, n.p.).

Expected Outcome: Achieve 85% enrollment, with 60% in quality programs.

Phase 2: Expansion (2028–2031):

Goals: Train 1 million additional teachers, upgrade 60% of Anganwadi’s, and regulate 50% of private pre-schools.

Actions: Scale CPD for 80% of teachers (NCTE, 2023, n.p.), expand Bal Vatika’s to 80% of schools (Times of India, 2023, n.p.), enforce regulatory frameworks (NCERT, 2022, n.p.), and conduct nationwide surveys (UNICEF, 2020, n.p.).

Expected Outcome: Achieve 90% enrollment, with 75% in quality programs.

Phase 3: Consolidation (2032–2035):

Goals: Achieve 100% teacher training compliance, upgrade all Anganwadi’s, and ensure universal access.

Actions: Meet 4-year B.Ed. requirement (NCTE, 2023, n.p.), integrate ECCE into school complexes (Ministry of Education, 2020, p. 15), allocate 10% of budgets to ECCE (UNESCO, 2022, n.p.), and monitor quality via NIPCCD tools (NIPCCD, 2023, n.p.).

Expected Outcome: Achieve 95–100% enrollment, with 90% in quality programs by 2035.

Feasibility Analysis

The 2030 target is ambitious given the 1.5–2 million teacher shortage, 7% budget cut in 2024–25, and data gaps (PRS Legislative Research, 2024, p. 5). Current training capacity (50,000–70,000 annually) must triple, requiring ₹5,000 crores annually for infrastructure and training, exceeding current allocations (Ministry of Women and Child Development, 2023, p. 22). State initiatives, like Uttar Pradesh’s Bal Vatika’s and Tamil Nadu’s Montessori classes, provide momentum, but national coordination is lacking (Government of Uttar Pradesh, 2024, n.p.; Government of Tamil Nadu, 2023, n.p.). A 2035 timeline assumes 15–20% annual budget increases, 50% digital training reach, and 30% infrastructure gaps bridged by PPPs and NGOs. Without this, universal access may extend to 2040, particularly in rural areas.

Strategies to Accelerate Progress

To achieve universal ECCE and ensure quality, proposed strategies include:

Scale digital training via SWAYAM, training 500,000 teachers annually, reducing costs by 40% (Ministry of Education, 2024, p. 8).

Leverage PPPs with NGOs like Pratham for 20% rural coverage, increasing access for marginalized communities (Pratham, 2024, n.p.).

Advocate for 10% education budgets for ECCE, supported by CSR and international funding (UNESCO, 2022, n.p.).

Integrate ECCE metrics into UDISE+ for real-time monitoring (Ministry of Education, 2024, p. 8).

Expand monthly ECCE days to 80% of Anganwadi’s, boosting parental engagement by 50% (Government of Tamil Nadu, 2023, n.p.).

Accredit 70% of private pre-schools by 2030 for quality compliance (NCERT, 2022, n.p.).

Target 100% enrollment in disadvantaged districts by 2032 via subsidies and mobile units (Government of Chhattisgarh, 2023, n.p.).

NEP 2020’s ECCE vision aligns with global evidence, showing $7–$12 return per dollar invested (UNICEF, 2019, n.p.). The IECEI study confirms quality ECCE improves primary outcomes, yet only 50% of programs meet standards (UNICEF India, 2022, n.p.). Fragmented governance, with ICDS prioritizing nutrition, leads to inefficiencies (UNICEF India, 2020, n.p.). The 7% budget cut contradicts NEP 2020’s 6% GDP investment call (PRS Legislative Research, 2024, p. 5). States like Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu show scalable models, but national coordination is lacking. Aadhar Shila’s play-based approach is promising, but teacher shortages and infrastructure gaps risk delays. Addressing data gaps and regulating private providers are crucial for equity and quality.